In preparation for my holidays, I have been learning some of the rudiments of sea navigation. Nowadays, boaters and professional seamen use the GPS for navigation. It is a remarkable piece of equipment, and is normally very reliable and does most of the chartwork. You programme in data like where you want to go, via where and what dangers you want to avoid. The device does all the calculations, and all you have to do is follow the course it gives – just match the figures on the screen with your compass bearing.

Seamen haven’t always had GPS, and sometimes a GPS device can fail or the satellite link is broken. All machines go wrong once in a while, and the more complicated they are, the more difficult they are to repair. You don’t just give it a “fourpenny one” like my old grandmother giving the old 1950’s TV set a bash on the side! It’s all very technical. So, you’re in a boat and the GPS stops working. You still need to know where you are – you need to know how to do it the old-fashioned way.

We are going to Fouras, near the Ile D’Oléron on the west coast of France. Those are sheltered and very safe waters, though not without things to watch out for like oyster farms, rocks that cut boats open like can openers, and the tidal currents. There are islands that look similar, and there is a real possibility of getting lost in my little dinghy. So, I decided to open this mysterious book. Navigation is observing the positions of landmarks, or if you are out of sight of land, the sun, the moon and the stars – and making calculations to find out where you are on God’s earth and going where you want to go without dashing your ship on the rocks in some forlorn place.

Dinghies stay inshore. My class of vessel requires me to stay within 2 nautical miles of a shelter, which can be a port or any beach where a boat can safely make landfall. I stretch things a bit, though I do take precautions. I haven’t yet the money for a portable VHF, so I am chancing it by having my ordinary mobile phone in a watertight bag on a lanyard around my neck. I have an oar, a fixed compass and an anchor of 50 metres of line. That takes care of what happens if my mast comes down because of a faulty shroud or forestay.

Today, I invested in three important pieces of equipment for coastal navigation. The first item is a hand sighting compass similar to this one:

This simple little gadget needs no electricity and doesn’t depend on a satellite network, but it will always do the job. You look through it at a landmark, like a lighthouse, a church steeple or a headland – just as long as you can identify the same on your chart, and you read off the compass bearing. It is very accurate. You take a “fix” on three objects and note it all down.

You then get your chart (or a photocopy under plastic as things get wet in dinghies) and find the three things you just looked at with your sighting compass. You relate the chart to reality by means of a Portland (or Breton) plotter, which looks like this:

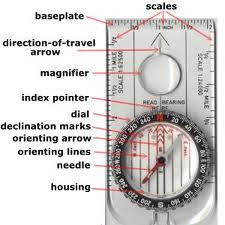

You can alternatively use the compass rose on the chart and parallel rules, but that is best when you have the luxury of a ship’s navigation table and dry conditions. Heave the boat to so that it doesn’t drift too much from the position you’re trying to find. A hove-to boat moves about a hell of a lot in the waves, but you get used to it! The Portland plotter, I have discovered, is the simplest way of finding your position and plotting the course to where you want to go. Actually, it works exactly like an orienteering compass:

You can alternatively use the compass rose on the chart and parallel rules, but that is best when you have the luxury of a ship’s navigation table and dry conditions. Heave the boat to so that it doesn’t drift too much from the position you’re trying to find. A hove-to boat moves about a hell of a lot in the waves, but you get used to it! The Portland plotter, I have discovered, is the simplest way of finding your position and plotting the course to where you want to go. Actually, it works exactly like an orienteering compass:

The orienteering compass is used by walkers, and all you need is the compass and an Ordnance Survey map. You turn your map to the north, and work everything out from that. That is something you can’t do at sea, because the boat is constantly moving. That is why we separate the taking of the compass bearings and plotting them on the chart.

I mentioned three things. The third is the pair of dividers, which you use to measure distances and read them off on the chart’s scale. Using a watch, you can then calculate your speed over a given distance.

Anything spiritual in all this? I could liken the Christian life to finding your way with great difficulty. Some churches use the compass as a symbol, like the TAC.

In the middle of the shield is the compass rose (or at least the cardinal points) superimposed by a cross. The link is obvious, and the symbolism is the universality of the Gospel and the Church’s mission.

In the middle of the shield is the compass rose (or at least the cardinal points) superimposed by a cross. The link is obvious, and the symbolism is the universality of the Gospel and the Church’s mission.

Another purpose of this article is to consider the way man has learned to measure and understand the earth since the dawn of history for the purpose of exploration and trade. The earth, the solar system, the galaxy and the universe are an incredibly complex piece of machinery, and working according to laws and predictable principles. Amazing, isn’t it – and all that couldn’t happen by accident.

Every time I take the boat out, it is a new spiritual experience with God’s creation. Now, I discover how man rationalises this natural beauty by means of science and mathematics. How wonderful, that God has endowed man with intelligence, and at least some goodness. I use technology that others use for warfare or exploiting nature beyond its ability to recover. I use it to make discoveries and commune with nature as few tourists would.

In one afternoon, I got the essentials of coastal navigation with the help of Youtube lessons from master navigators. There are many other tricks like the use of waypoints and running fixes, and I am still a little baffled. I just need to work at it. After that will be the offshore kind of navigation using a sextant and a chronometer – but for that, I will need a very different kind of boat! Patience…

I have been doing some experiments on land, but with an inaccurate map. I discovered that the position of my house was in the middle of the road, but that the triangulation was actually accurate to about 40-50 feet. That would not be bad at sea! Civilian GPS is hardly more accurate than that!

I am confident I won’t get lost during my little forays in my dinghy – and I’ll do a new article when we get back from our holidays.

Wishing you and Sophie a blessed and refreshing holiday.

You might be interested to know that, for precisely the reasons you mention, we weren’t allowed to use the GPS in the Navy – the skills required to cope without it are far too perishable if you don’t use them every day. So, when I was a young officer a couple of years ago, we’d do morning and evening starsights, and the solar zenith, then sit down with the sight reduction tables, log tables, almanacs and spherical trigonometry to work out where we were.

I left in 2006, and, to rather prove the point, I genuinely wouldn’t know where to start now!

That’s why I started to learn without GPS. It is like when I was a schoolboy having to use a slide rule and books of sine and cosine tables even though electronic calculators were already available in the early 1970’s. There is a compromise – using sighting compasses and sextants and a computer (with the appropriate software) for the calculations – on a nice dry navigation table in a yacht (or bigger vessel). That takes care of the absence of GPS signals from the satellites, but not failure of your own equipment. I’ve seen some very interesting inventions on the Internet over the past few days.

Do you still sail even though you have left the Navy?